A Hand Loom Weaver |

Many of our Bancroft ancestors from Yorkshire were Hand Loom Weavers, working from home and trying to exist on a very low standard of living, but surviving…but only just, in the early 18th century. Their way of life was however about to change for ever as weaving textiles moved from a cottage industry to mass production in the new Woollen Mills springing up in every town in Yorkshire.

Many had little option but to seek work in the mills, often at any price, as starvation for them and their families was staring them in the face as the hand loom work largely dried up.

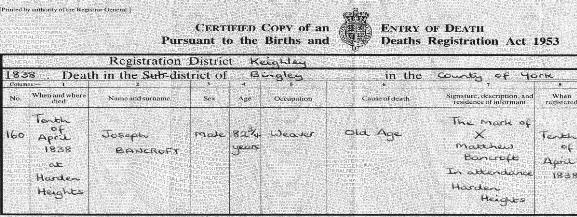

My G/G/G Grandfather Joseph Bancroft [1755-1838] was a hand loom weaver all his life. He had 4 children with his first wife, Judith Smith, who died at the early age of only 34 years, and then went on to have a further 11 children with his second wife Ellen [Nelly] Bradley. Even at the time of his death at the grand old age of 82 years was still listed as a weaver.

Joseph Bancroft's death certificate |

An insight into the living conditions of a hand loom weaver in the nearby

village of Heptonstall, is graphically described in the following extract from

the book 'The History of the typhus of Heptonstall Slack' by S Gibson:

" The reminiscences of a Heptonstall Handloom Weaver, born in 1809,

shows just how low was his standard of life in this period. His cottage had no

under-drawing, was cold and damp, and snow blew in during the winter. His

bedding consisted of two cotton blankets, a rough cotton quilt and pillows

filled with chopped straw. Furniture consisted of a three-legged table, two old

chairs, two three-legged stools and a chest of drawers. Food was monotonous and

poor and utensils were scanty. His porridge pan doubled as a frying pan. Owing

to a shortage of knives and forks, some of the family ate with their fingers.

There were a few broken cups and saucers, and old teaspoon and a jug for

fetching milk. The diet consisted of porridge, old milk, treacle, potatoes and

oatcake. For dinner he had fried suet with salt and water for gravy.

occasionally he had tea or coffee, but normally drank a brew of mint, hyssop or

tansey from the garden. He worked an 11 and a half hour day for 6/6d per

week."

A weaver's cottage with hand loom |

A local poem written anonymously at that time by an out of work weaver sums up the desperate plight of these poor people as they had to accept the poor wages paid by the new mill owners.

'Draw near, honest people, of every degree

And listen a little, I pray unto thee

While I shall attempt to unfold in my tale

A few of the tricks which in England prevail

Then first, for the weavers, a set of poor souls

With cloths on their backs much like riddles for holes

With faces quite pale, and eyes sunk in the head

As if the whole race were half famished for bread

Indeed, when these wretches you happen to meet

You think they were shadows you see in the street

For thin water-porridge is all they can get

And even with that they are often hard set…..

The weaver stands staring, the master shouts out

“ Come take this five shillings, or else go without

For charity’s sake, I employ you, you know

Or else to the workhouse you’d soon have to go”

At last the poor weaver is forc’d to submit

This workhouse has frightened him out of his wit

So take it and think so, tho’ it only small

Five shillings are better than nothing at all'

By the late 17th century many hand loom weavers, perhaps those less skilled, were only employed when work was plentiful and this group needed work such as farming to put food on the table. The Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, and after this time the weaver’s plight worsened significantly, not just due to mechanisation as powered wool looms were slow to develop but primarily because the labour market increased dramatically when soldiers, sailors and other workers were laid off as the war machine came to a stop. Employers assembled the weavers into hand loom ‘factories’ and cut the wages paid for their labour. Riots and demonstrations took place as the weavers, both of cotton and wool, demanded a living wage. They were largely unsuccessful in their demands.

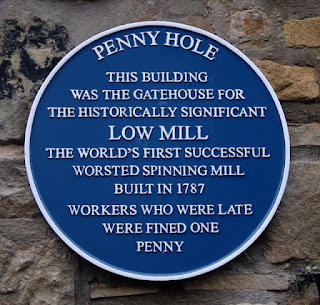

By 1826, the weaver’s plight became so desperate that riots started at many local mills in Northern England with mill equipment being destroyed and on the morning of Wednesday, April 26 1826 one group of determined men left villages in the Laneshaw Bridge area near the Lancashire/Yorkshire border to march to Addingham in Yorkshire and smash the newly installed power looms in Low Mill. Most of them were hand loom weavers. They had been without work for several months and were starving.

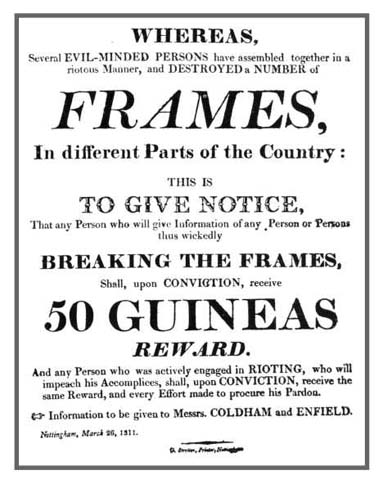

Riots had started in Lancashire on the Monday, but now this new group of rioters was joined by Yorkshire men from places such as Addingham, Cowling, Keighley and Eastburn and mill owners posted notices offering rewards for anyone who could provide information leading to the conviction of rioters.

Mill owner's reward poster |

Jeremiah Horsfall, who ran Low Mill in Addingham knew an attack was likely and had asked William Vavasour, a JP, for military help. As he didn’t know if help would arrive in time, Horsfall set off to Leeds on horseback to ask for the Dragoons. In the meantime he had left his manager, Timothy Lawson, to defend the mill with the help of a few workers.

About five o’clock in the afternoon 400 to 500 men marched through Addingham to Low Mill armed with hay-forks, cudgels and axes.

Low Mill, Addingham blue plaque |

About 150 approached the mill and asked for admittance to smash the looms. Mr Lawson refused, but said he would give them money for food. They said that if the mill was defended they would throw all the defenders out of the top windows. Quickly the door was bolted and the rioters started throwing stones at the windows. These had been barred and stones taken to the top floors to throw down on the attackers.

Eventually, as the stone throwing continued without effect, the defenders fired their sporting guns over the heads of the rioters and then into the mob. Several were wounded with two taken back to Colne and eleven cared for in the village. One defender lost two fingers when his blunderbuss exploded.

Eventually the mob dispersed after Ellis Cunliffe Lister, a magistrate and owner of another local mill arrived and read the Riot Act. Special constables were sworn in and some arrests of local men were made.

The following day men set off again from the Laneshaw Bridge area, but when they arrived on the slope looking down to Addingham Low Mill they stopped. A newspaper report estimated that there were several thousand people assembled on the hills round the village.

After a short debate the men turned back, but about 200 decided to march to Skipton and then on to Gargrave. Ellis Lister ordered the captain to take some prisoners. The other men continued through Skipton in military style and collected more support on the way. Their target was High Mill in Gargrave. Joseph Mason, who owned the mill, had just installed 25 power looms to replace the hand loom weavers he had previously employed.

Mason knew the rioters were on their way, but made no attempt to defend his mill. When they crossed the bridge in Gargrave about nine o’clock he approached them and offered money for food, but they refused. They marched on, broke down the mill door and smashed the 25 looms and other machinery.

The local magistrates had been busy swearing in large numbers of special constables and six of the rioters were arrested.

How many of the men who broke the looms in High Mill came from Lancashire that morning is impossible to say. From the evidence collected about those rioters who attacked Low Mill in Addingham the previous day it would seem most were local men.

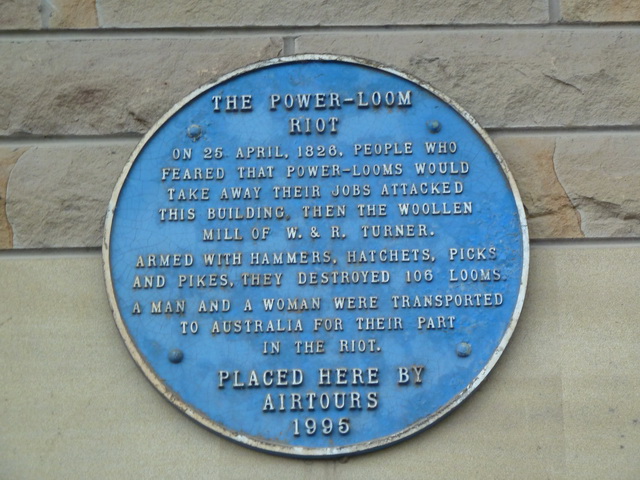

The following week rioting spread to Bradford mills the rioters were dispersed on the Monday after breaking the windows, but attacked again on Wednesday, May 3. As they were expected, the mill was defended by soldiers who killed and wounded men and boys.

Bradford mill blue plaque |

Though Parliament was against any state support for the starving, charity was encouraged, and the Lord Mayor of London had chaired a meeting with the purpose of raising money to help the poor in various parts of the country. Those attending included the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of London.

Among the first sums soon to be distributed was £200 for the Gargrave area.

Later, Joseph Mason, the Gargrave mill owner, applied to the local authority, for compensation for the breaking of his looms. His case was heard on July 18 and was given £300 compensation. This meant that some of the attackers would have had to pay a proportion of this if they rented or owned property in a local parish.

Arrests by special constables were made after the Gargrave attack and, though several men were questioned by local magistrates, none were sent to York Assizes. However, five men arrested after the riots at Addingham were sent under military escort to York Castle and three were sentenced to death though probably only served prison sentences.

Following these riots textile mills throughout West Yorkshire were garrisoned by soldiers for several weeks, but there were no further disturbances locally, although rioting continued both in Yorkshire and also at the Cotton Mills in Lancashire as late as the 1840’s.

Although I have no evidence that Bancroft men took part in these riots, it seems likely that they were involved, as there were many hand loom weavers struggling to survive at that time, and their cause for a decent standard of living was lost forever as the mills went from strength to strength.

There was however a silver lining to this story about the decline of hand-loom weavers. A boom occurred in the supply industries to the new Woollen and Cotton Mills of Northern England as the following two adverts show. One local company, Hattersleys of Keighley, had a worldwide reputation for the production of Weaving Looms and employed many people both locally and in assembly abroad, including some of our Bancroft ancestors who would previously have worked in the mills.

Another local business which benefited from the Mills was the production of weaving shuttles, which one local Bancroft family were heavily involved with, and I wrote an article about this some time ago, which can be read HERE.

Here is a picture of a shuttle with the “Bancroft” trade mark on it.

To finish this article, here’s another poem written in dialect by a weaver summarises how he was now left in despair and starvation:

‘Aw’m a poor wayver,as mony a one knaws

Aw’ve nowt t’ate i’th’heawse, un’ aw’ve worn eawt my cloas

Yu’d hardly gie sixpence fur o’ aw’ve got on

Meh clogs ur’ baws’n, un’ stockins aw’ve none

No comments:

Post a Comment