|

| Oatcake making in the home |

The consumption of oatcakes, also known as havercakes, was very much a staple diet for many Bancroft individuals in the 17th-18th century. When many were living hand to mouth on a very small income. Oates was about the only cereal crop they could grown on their poor quality small piece of land.

There were Bancroft families who made a living from making and selling oatcakes from their homes. One such individual was Joseph Bancroft [1838-1890] who lived in an area called Lees, in the Bingley Parish area, although geographically it is nearer to Keighley.

Joseph was the son of Joseph and Rachel Bancroft, who also lived in the same area and Joseph [Snr] was described as a 'Sawyer of Wood' on census records. His son Joseph started his working life as a 'worsted spinner' on the 1851 census in one of the many local mills, and went on to work alongside his father as a sawyer in later census records.

|

| 1851 census |

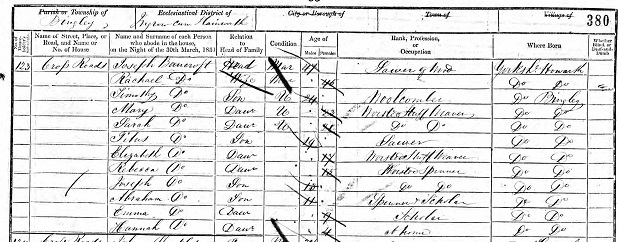

He married Mary Greenwood from the Trawden area of Lancashire in 1873, and by the time of the 1881 census Joseph and his family were still living in the Crossroads area, and he was now described as an 'oat bread baker'

| 1881 census |

Joseph died at the relatively young age of 52 years, and was buried at St John's Church in Ingrow, Keighley.

The process produced a floppy, elongated, flat bread that was then hung over the slats or strings of a bread creel suspended from the ceiling and left to dry. Once dry it became crisp and could be stored for months.

Most homes had a bakestone in the early 19th century but if a farmer's wife did not have time to make her own oatcake she often employed someone to do it. Women would travel from farm to farm spending all day making large batches, one old lady recalling that she thought she had made enough in her lifetime to cover 500 acres.

Oatcakes were eaten both soft and hard. Whilst soft they were spread with butter, treacle or honey and rolled up to be eaten. They could be toasted and spread with butter. Hard oatcakes were eaten with cheese or softened in a bowl of milk. Oatcake sop was a family favourite, the cake dipped into the dripping pan from the Sunday roast. Inns kept a ready supply and customers broke them up and dunked them in beer. On the Craven/Lancashire border pubs served stew and hard until about 20 years ago. A crisp oatcake was broken in half to sandwich a slab of stew (a potted meat made from shin beef and cow heel jelly) and sliced onion.

The original oatcake, went out of fashion many years ago, as families became more affluent and stopped baking in the home, to be replaced with the oatcake we know today, which is a small round biscuit which is usually eaten with cheese and shows no resemblence to the oatcake of times past.

No comments:

Post a Comment